Culminating experience for Design Thinking Course

Problem: Do students cheat at Dartmouth? Who? How? Why? If so, how might cheating be reduced?

For the culminating experience for ENGS 12, Design Thinking, we were broken into teams. Each team was given a different, Dartmouth-relevant challenge to solve using a design-thinking approach. We were asked to explore cheating behavior, and propose a way to reduce cheating at Dartmouth.

Solution: Cheating behavior is most often driven by moments desperation when student's resources have run out and there is a mismatch between a student's perception of the grade at stake (high) and the academic relevance of the activity (low). We surveyed students and current methods being used by professors to combat cheating and developed detailed reccomendations for professors and faculty who wish to sustainably reduce cheating at Dartmouth.

Role:Researcher and Designer

Impact:Our professor found our insights and research on this challenging problem to be especially impactful. He asked us to present our findings and policy implications to the Provost and to Dartmouth’s Division of Student Affairs.

After interviewing 48 students and one professor, we saw clear patterns in who cheated, and why. We used these commonalities to create three personas: the Pro, the Angel, and the Relativist. Pros see cheating as a valid use of their own resources, and cheat like it's their job. Rare, confident, and adept at exploiting opportunities in the system, their behavior gave us insight into what makes it possible, or even easy, for a motivated person to cheat. Unless we overhauled the system, it was going to be hard to stop these agents from cheating. Angels never cheat, no matter the cost. Also rare, they perceived themselves as martyrs, denying opportunities to cut corners, sometimes at the cost of sleep, wellness. Most students seemed to fall in to the category of Relativists, who feel that breaking the school's honor code is a moral gray area. Because of their prevalence and context-based behavior, we saw relativists as the best candidates for intervention.

Relativists are most likely to resort to cheating when the stakes feel too high and course content feels arbitrary or irrelevant. Though most students did not feel proud of cheating, they seemed to find it justified in what they see as a broken system. Importantly, we also realized that students have limited resources, and that cheating most often occurred when it seemed like those resources were exhausted or unbalanced: most who cheated felt as though their backs were against the wall.

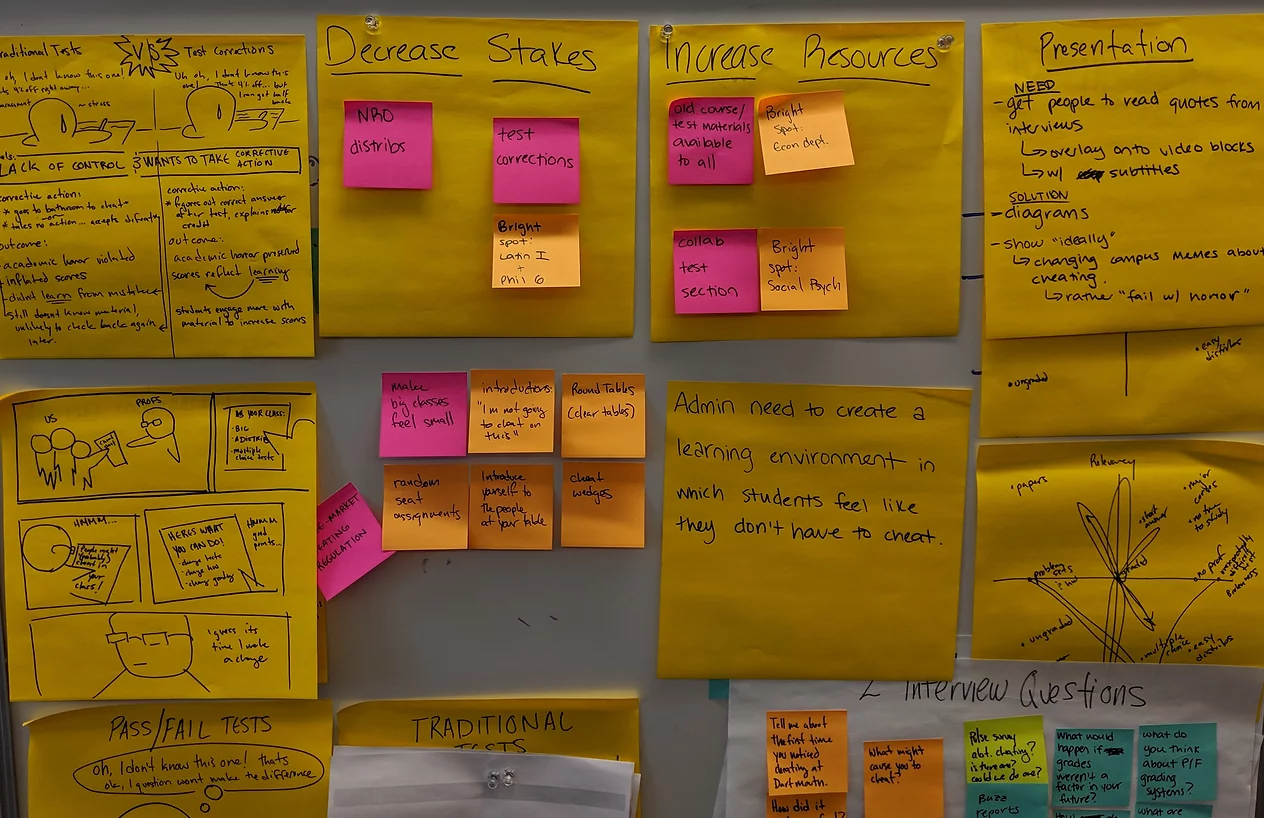

Using students as a resource, we identified several methods to reduce testing stakes and increase resources available to students that were already being used by some professors. We proposed expanding these practices, as well as taking other measures to engage students with meaningful content. If you're curious about our specific reccomendations, you can read our full Report on Reducing Cheating at Dartmouth.

Though I think we diagnosed the situation well, looking back, there are some things I wish we had done differently. First, our solution could have benefited from even more information, especially from more diverse perspectives. During our data collection and testing phases we focused heavily on the student perspective, but Professors and Administrators are sure to have valuable perspectives on cheating behaviors as well. Further, any changes to the teaching environment will be more effective with professor and administrator buy-in, and will require a baseline understanding of professor and admin attitudes for implementation.

Second, we decided early on that our intervention should occur at a course-structure level, but, our interviews support an attitude level intervention as well. It is also clear from our presentation to the Judicial Affairs Department that the administration is unfamiliar with the scope of cheating and student attitudes surrounding it. After gaining distance from this project, I wonder how one might change student's attitudes about cheating.